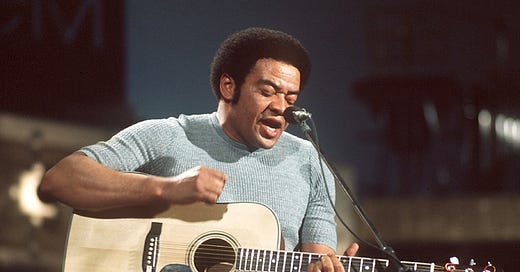

Saying goodbye to Bill Withers, the Donald Glover experience, The revolution is already underway.

Watch: Bill Withers Live (BBC) on YouTube

BBC, 1974

Runtime: 29:24

If i’m honest, i’ve been trying for three days to come up with a good way to express how very much I love the music of Bill Withers, and how deeply it saddens me to know that he’s gone. I’ve written 9ish versions of this, each one longer and somehow less effective at capturing the essence of what he meant to me, and music, and the culture.

There was a version that used the Kansas April thunderstorm as a metaphor for the kind of “all at once” swell of the voice, the guitar, the songwriting, and the groove exploding onto the scene in the early 1970s. “Harlem” was the first song on his debut album. Then “Ain’t No Sunshine” is the second song. Then “Grandma’s Hands” is the third song. Those are his first three songs…what on earth?

Then there was another version of this piece that just explored the first 5 seconds of his most iconic songs, spotlighting the magic of how in two beats you know them all instinctively. I tried to explore the warmth of comfort and knowingness and familiarity that washes over you when you know a song in your bones; the ones you sing along to because that’s what you do when you’re in that place. That feeling is like an oversized sweater, or your college sweatpants, or the feeling of someone you love scratching your head.

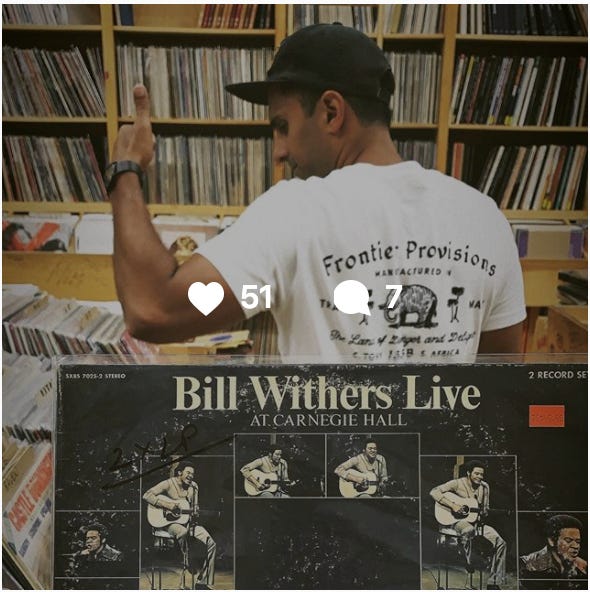

Another bit was all about how last Fall I went to Seattle primarily to visit my dear friend Julian, his wife Katie, and their dog. The secondary objective of the trip, was that Julian is the most accomplished and competent record sleuth I know, and i’d been on this three-year hunt for Bill Withers Live at Carnegie Hall from 1973, with no luck. I knew if there were any city to have it and any person who’d know where it was, it’d be Seattle and Julian, respectively. After exploring 6+ record shops, our search bore fruit.

Every day since, it’s been the thing in my modest collection to which i’m most attached.

But the reality is, none of those stories get at the essence of what was so special about Bill Withers because they leave out the reality of who Bill Withers was. As the few available profiles of him reveal, he was a man completely uninterested in fame. He was weary of the music industry, weary of celebrity, and defiant in his insistence to not participate. And so it was, that a person whose music has been central to the last 50 years of American culture, spent the last 35 of them in intentional obscurity, allowing his work to speak for itself.

The only conversation he intended to have with the world was that which he recorded in those 14 years in the 70s and 80s. This BBC recording of Withers and his band playing a 30-minute set interspersed with his short stories to stitch the setlist together is an absolute treasure. It presents him as he so clearly intended to be perceived; a simple man of simple taste, exceptional talent, and real personal conviction. To watch him perform is to have every important question you could ever want to ask him, answered. He seemed to have lived a full life on his terms, and didn’t have a whole lot more he intended to say to the rest of us.

So why am I so upset that he’s gone? He was really just a stranger right? I suppose it’s because he never really seemed like much of a stranger to me, but rather somebody i’d just not yet had the chance to meet in person.

Listen: 24.19 by Childish Gambino on Spotify

I think we’ve reached a point where we feel collectively like we need to at least check-in on everything Donald Glover makes, right? Even when it’s weird. Maybe especially when it’s weird.

His latest album 3.15.20 is weird. I say that both because it’s true, and because it’s what he wants me to say. The album title is its original kinda sorta release date, but then it was online and then off, and then onto a streaming service a week later. The track names are all weird numbers, except one of them. There isn’t one specific sound or vibe presented here; rather a patchwork quilt of ideas and experiments. Results vary. From the pretty good (35.31) to the bad (53.49), and the criminally derivative (19.10).

But “24.19”…that one is special.

It’s an 8-minute soul meets synth odyssey that, were it not for the incredibly 2020 lyrics, could credibly have been plucked out of 1982. The vocals are like the result of a ProTools project to find the exact center point between Gil-Scott Heron and Smokey Robinson. In the tradition of the unapologetically 80’s pop rock tradition, it’s breathlessly overindulgent, every single instrument on it is overplayed, there are like 7 distinct movements in this one song, and it is terrific in every way imaginable.

“24.19” like “Redbone” that came before it and the “So Into You” cover and “Urn” before that and “So Fly” before that is a reminder that the musical foundation that undergirds everything Childish Gambino does is the stuff his parents played in his Atlanta household as a kid. His best work harkens back to those roots; the spoils of a childhood in which funk was a first musical language.

I was intensely curious how Gambino would follow up his last studio album. Would it be more “This is America” or Awaken, My Love! And now that we’ve got the answer, i’d like to simplify my expectations/requests henceforth. I don’t much care what kind of experimenting he wishes to do, I just hope he’ll sprinkle in a bit of stuff that sounds like this.

Read: The Revolution is Underway Already in The Atlantic

In hindsight a revolution may look like a single event, but they are never experienced that way. Instead they are extended periods in which the routines of normal life are dislocated and existing rituals lose their meaning. They are deeply unsettling, but they are also periods of great creativity.

At present, America is a bit like a snow globe that’s been given a proper shake. While there are considerable uncertainties across nearly every facet of industrial and domestic life, one thing is certain: there is no doubt there will be some meaningful changes to our worlds in the months, years, and decades that follow this global pandemic.

There are questions to be answered about our government’s preparedness and response to this global health crisis.

There are questions to be answered about our manufacturing sector and our economy’s dependence on China as our relationship with the world’s other super power continues to deteriorate precipitously.

There are questions to be answered about the rugged individualism that has been a cornerstone of the American ethos, as a whole generation of young people begin to turn their collective backs on a blind allegiance to capitalism.

There are questions to be answered about religious freedom and what happens when the faith of some is an existential threat to others.

There are questions to be answered about the long-term impacts of a devastating pandemic that seems to be, unsurprisingly, disproportionally affecting the most vulnerable communities. (exhibit a, exhibit b, exhibit c)

The answers to these questions and so many others will be incredibly influential in determining what the sociopolitical culture of America looks like over the next decade.

And unlike so many other times in recent history, it feels like so much is up for grabs.

In this piece, Indiana University History Professor Rebecca Spang uses 18th century France to help illustrate the kind of narrative-altering change that’s possible in the wake of these moments. It’s a reflective and sober exploration of the ways in which our worlds can shift so quickly once agitated.